Ultra processed food is a feminist issue.

From the kitchen to our health to the Earth herself, it's time for a change

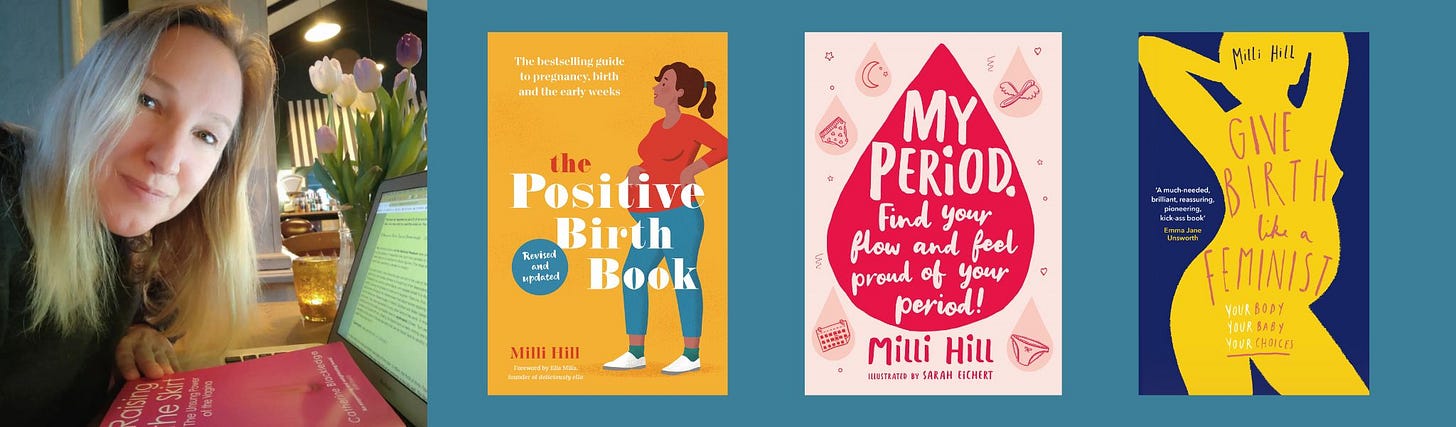

Tonight I’m giving a talk for the feminist organisation FiLiA about my forthcoming book, Ultra Processed Women. FiLiA, if you haven’t already come across them, are a fantastic charity, who do all kinds of amazing work (see their website) and also run an unmissable conference, where all the best feminists come together and get both very serious and very silly, all at once and over a whole weekend. I highly recommend it!

I’m going to talk about ultra processed food (UPF) and how this specifically affects women. But first, I’m going to give a little potted explanation of what UPF actually is. Throughout my talk I’m going to try and keep in mind the same question that underpins my book, ‘But what about women?’.

It was this question that got me interested in the issue of UPF in the first place. The conversation about it felt quite male dominated, and it was consistently being presented as a problem for ‘people’s’ health that ‘people’ would have to do something about. Hmm, that’s interesting, I thought. What about women? And also, when it comes down to the wire, is this going to be yet another thing to add to women’s already massive to-do list? Effectively, are busy knackered mums like me going to be going round the supermarket in a state of stress, frantically looking at labels and unable to put anything apart from broccoli in the trolley?

So anyway, let’s clear up the basics: what UPF actually is. I think a lot of people assume it’s ‘junk food’, but it’s slightly more complex than that. The definition of UPF was created by Brazilian researcher Carlos Monteiro in 2009. He was concerned about rising obesity rates and wanted to categorise food in terms of the amount of processing, so that the impact of different types could be more easily studied.

So here are the four Nova categories.

Nova 1. Unprocessed or minimally processed

Food with very little done to it. Whole foods. Fruit, veg, meat, eggs, milk etc.

Nova 2. Processed culinary ingredients

Extracted from Nova 1 foods or from nature, and not usually eaten by themselves. Butter, oil, salt, sugar, maple syrup etc.

Nova 3. Processed food.

Made by combining foods from category 1 and 2, and putting them through processes like baking, fermenting, boiling or canning. Cheese, fruit juice, apple sauce, homemade / artisan bread, biscuits etc.

Nova 4. Ultra processed food.

Bear little resemblance to Nova 1 foods. Industrially processed, made from substances derived from food, with long lists of ingredients, and additives.

It’s a mistake to think that only ‘junk food’ or ‘unhealthy food’ falls into Nova 4, ultra processed food. In fact, lots of UPF is marketed as a healthy option, and often it’s particularly directed at women, for example ‘low fat’ or ‘diet’ food. ‘Plant based’ food is another massive red flag - many (not all but a majority) of these items are UPF.

The second thing to know about UPF is that there was a very important study, ran by someone called Kevin Hall, in 2019 in the USA. Hall had heard about the Nova groups and UPF and thought the idea that these foods were responsible for obesity was a load of rubbish. He set up a randomised controlled trial in which ten women and ten men spent 4 weeks living in a clinic and eating a prescribed diet. The group was split in 2 and spent 2 weeks eating a UPF diet and 2 weeks eating a diet of whole foods cooked from scratch, and then they swapped. They could eat as much or as little as they liked on both diets.

On the UPF diet, participants ate more - around 500 calories more per day, ate faster, and gained weight, around 2lbs or 1kg.

So Hall had to review his stance completely. This study was really significant. It seemed like there really was something about UPF that was affecting people differently.

What that ‘something’ is is still being researched and debated.

From everything I’ve read, I would suggest it’s a combination of factors. 1) UPF is hyperpalatable and addictive (once you pop, you can’t stop). 2) Some UPF ingredients, for example emulsifiers, may affect the microbiome. And 3) It displaces whole foods in our diet. (if you eat a McDonalds you are missing out on nutrients that you simply won’t be hungry for).

But what about women?

Well, categorising UPF has enabled much research and there are so many ways in which UPF is being demonstrated to impact our female bodies.

For example, women are more likely to be obese as adults, and obesity increases the risk of many major diseases: heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes and more. And UPF increases the risk of obesity. In the USA, the number of women with severe obesity (defined as a BMI of 40 or over) is double the number of men with severe obesity. It’s worth being clear, though, that UPF increases your risk of major diseases if you are not obese, too.

Women are also more likely to have food related mental health issues. Those with eating disorders that involve binging, such as bulimia and binge eating disorder, are likely to use 100% UPF during binging episodes, and have also been found to have diets high in UPF – as high as 70%. These two types of eating disorder have also been consistently shown to have strong associations with childhood trauma and abuse, which we know is far more prevalent in girls, in particular sexual abuse, which is over three times more likely to happen to females. And girls who have experienced childhood sexual abuse are over twice as likely to go on to develop binge eating disorder, and nearly three times as likely to develop bulimia.

Depression is twice as common in women as it is in men, for reasons we don’t fully understand. And strong links have been found between UPF and depression, with research recently published in the British Medical Journal suggesting a diet high in UPF increases risk of depression by as much as 22%. Another piece of research into middle aged women found that the increased risk of depression in this age group was 50%. And in another, in which participants already had depressive symptoms, support to change diet away from UPF led to a third of people meeting the criteria for remission. And of course, as is becoming well documented, women may also find that when they report poor mental health they are not listened to or their hormones or stage of life take the blame.

Women are far more likely to suffer from autoimmune disorders (around 80% of sufferers globally are female) it’s thought because of that extra X chromosome. Basically our extra X works largely to our advantage, providing us with a back up immunity, explaining why we live longer and are more likely to survive premature birth, disease, traumatic injury, adversity, and famine. With autoimmune disease, however, the extra X gives our immune cells double the chance of misfiring and attacking the wrong target (ourselves). And UPF has been shown to impact on several autoimmune conditions: a recent study showed those consuming UPF in high amounts had at least a 50% higher chance of developing Lupus, for example.

The areas of women’s health potentially impacted by UPF are too long to list in this brief talk, they have filled a book. But, for example, a few other startling statistics are:

In menopause, a diet low in UPF and high in plants has been shown to decrease symptoms by 34% (regardless of whether the woman chooses to take HRT or not)

In pregnancy, a high UPF diet has been shown to double the risk of miscarriage.

UPF has a negative impact on both female fertility and male sperm count.

UPF has been associated with heavier and more painful periods, and worse PMS.

UPF increases the risk of developing and dying from female cancers

What’s really interesting to me is how women, and even feminism, has been co-opted by food companies in order to sell us an idea of freedom, whilst at the same time they are effectively making us sick.

In the book I’ve delved into some of the history of the marketing of UPF. One thing of note is that women, in particular those campaigning on environmental issues, have raised objections to UPF and been quickly discredited, for example in the USA, Dr Joan Dye Gussow, organised a Food Day in 1975 (that’s nearly 50 years ago!) and declared that UPF was not really food at all, but forces from Big Food condemned her and the day for ‘creating anxiety’ and ‘disseminating information’. Please do tell me of any other similar activists who spoke specifically about food if you know of them, their history seems quite hard to find.

Meanwhile, UPF manufacturers from the 50s onwards sold women an idea: UPF could liberate them. And to sell this idea, these major global corporations took on female identities, the most famous of which is still going today - Betty Crocker.

Newsflash: Betty Crocker is not, and never was, a real person. She was one of many so-called ‘live trademarks’, invented by food companies to sell their products. These live trademarks had a specific recipe: “Ideally, the corporate character is a woman, between the ages of 32 and 40, attractive, but not competitively so, mature but youthful-looking, competent yet warm, understanding but not sentimental, interested in the consumer but not involved with her”, explained a trade publication in 1957. It’s ironic, isn’t it, that these marketing tools were on the one hand presenting the image of the perfect housewife, whilst at the same time carrying the message that cooking and baking is a waste of women’s time? And we still see them in modern advertising, for example the Dolmio grandma, kindly and twinkly and Italian, making food ‘just like mamma used to make’. Dolmio is made in Wales I think!

Rosie Boycott, one of the founders of Spare Rib, has explored this issue from a personal perspective in an interesting article in the Guardian which you can read here. She talks about how in the 70s, Spare Rib were very keen not to have any recipes or suggestions about home cooking, because they saw this as key to liberation. “As an early subscription offer for the magazine, we printed a purple dish cloth, which, though tattered and a bit torn, is still in use in our home today”, she writes, “Written on it are the words: "First you sink into his arms, then your arms end up in his sink."“

However, having evolved in later life into a passionate campaigner on food and the environment, Boycott wonders if the persistent message that ‘the kitchen’ was a place women need to escape from, was in some way damaging. She realises the damage to health of ‘ready meals’, and writes, “It may be fanciful to lay the blame for this at the feet of the early feminists, but, without a doubt, our struggle to free women from the sheer drudgery of housework was a small link in the chain.”

The way I see it, feminists were not to blame. (Well I feel I have to see it like that. I’m aware women already get the blame for all sorts of sh*t that wasn’t their fault!). Instead, I think food companies saw an opportunity with feminism and entwined their products with the idea of freedom in a way that was very appealing to women at the time. They actively used slogans like ‘Wife Savers’, and, “Liberate mum, take home some Kentucky Fried Chicken today!” But in fact, it wasn’t food, or cooking, that was keeping women ‘in the kitchen’ - it was patriarchy. And I’m not 100% convinced by this idea that UPF has liberated us either? The reality seems much more complex - but if the plan was to give everyone more leisure time that definitely doesn’t seem to have worked - women now feel more overstretched than ever.

So I wonder if food and cooking is something that we need to actively reclaim? There is a lot of talk of ‘quitting UPF’ or ‘giving up processed food’ but I prefer to reframe it in terms of, not what we are giving up, but what we might gain if we turn back towards real food. There is something about UPF that chimes exactly with other issues that we as humans are currently facing:

mindless consumption

quantity over quality

lack of human contact

disconnection from nature

never having enough time.

It’s that swipe up, discard, swipe up, endless consumption vibe that we are all getting a bit tired of but can’t seem to stop doing. Food out of a packet, with which we have no connection, and which with its industrially pulverised chemical ingredients doesn’t really have much connection with nature, seems to be another dimension of this slightly dystopian direction of travel. So cooking and sharing real food can become quite an act of resistance, a refusal to become ‘ultra processed women’.

There is also a huge environmental angle that I’ve explored in the book which it would be remiss not to touch on briefly as we are talking about the feminist angles. As well as being hugely damaging to our bodies, UPF is also incredibly damaging to Mother Earth. From palm oil and soy destroying rainforests and displacing indiginous peoples; to packaging waste; to carbon emissions; to intensive farming - the heartless damage to the planet of our current food systems feels deeply exploitative and patriarchal. It’s also true that as humans our health and survival is dependent on the health and survival of the Earth - we need the soil, and we need the soil microbes, to grow our food and feed us and our gut microbes. We live in a dynamic two-way relationship with the earth and we need her more than she needs us. At the moment that relationship has become exploitative - we have forgotten how to be mindful of what we take from the earth, we’ve forgotten how to be grateful - we’ve lost connection. She has become a resource to be exploited, mistreated, never thanked, and cast aside when we have depleted her. As women, this is somewhat relatable.

But, as hard as this all is to contemplate, it does also mean that the simple act of changing the way we eat is a form of environmental activism. Some call this ‘regenerative eating’. I find it really inspiring to think that my grocery choices could make a real difference not just to my own body but to the future of the planet. What we need to do as women is make sure all these messages come across but at the same time ensure that women are not saddled with the grass roots job of making dinner every night! (unless they want to).

Thanks for this and good luck with your FiLiA talk tonight! I'd love to be there.

Your book and mine on women's diet and weight battles as 'the fatter sex' programmed, with a slower metabolism, to store 50% more body fat than our brothers are, have a lot of cross-over material. I look forward to reading yours.

You asked if we know of any other women pushing against Big Food back in the 70s and I immediately thought of Susie Orbach, who was one of the first eating-disorder counsellors and of course the first to see that women have specific and indeed feminist issues around food and fat. In my book I quote the following she wrote on the feeding challenges for mothers from her first edition of 'Fat is a Feminist Issue' (1978):

"[As mothers] women experience particular pressure over food and eating… To the tune of billions of dollars a year, the food industry counsels [a mother] on how, when and what she should feed her charges… [such] that the housewife is presented with a list of ‘do’s’ and ‘don’ts’ so contradictory that it is a wonder that anything gets produced in the kitchen at all. It is not surprising that a woman quickly learns not to trust her own impulses, either in feeding her family or in listening to her own needs when she feeds herself."

I agree women need to get back to cooking (many of us never stopped), ideally with family help with the more tedious bits, in order to avoid the various traps set by Big Food, like the 'sugar free' fruit juices sweetened by fruit juice concentrate that we now know is essentially sugar, with the skins - where all the nutrients and fibre are - removed in the processing.

I totally agree veganism has become a Big Food con, largely based on UPFs wrongly sold as healthy and planet friendly, and I have seen first hand its terrible effects on young women, from ruined hair to, early onset osteoporosis and unnatural breast growth attributed to soya beans mimicking oestrogen in the body. Definitely more research and writing needed there.

It's a bloody big battle to be sure. Bigger than trans, in many ways. I'll drop the link to my book here, if you don't mind. Hopefully we can have a longer chat about the battle at some later time: https://www.amazon.com.au/dp/0473697769?ref_=mr_referred_us_au_nz

Cheers, SJ :-)

The first thing that struck me is that in just four stages we go from "food" to something that barely resembles the thing it derives from in either the way it looks or what it provides our bodies!

I was raised very much in a "you are what you eat" and preparing food takes from 2-4 hours of my day depending on what I'm cooking/preparing for - I do this because my health and that of my family is important to me and was ingrained in me from a young age to eat "real food". I can see how my life would be easier with packaged foods but having lived on variations of processed food when I was at university or on work trips or similar I know I quickly feel "sluggish" and tired and like I need a massive salad to get myself moving.

The illusion that upf is "easier" is one the patriarchy has easily convinced women of... Removing the skills passed from mother to child (usually girls but also boys) of "how" to cook even the simplest things, so many women I know just don't have the confidence to cook let alone teach their children! "Home economics" as a subject is no longer taught at school - the GCSE food technology classes I had in the late 90's involved more "designing" packaging for food products than actual cooking and I was marked on the presentation of my drawings (and I am crap at art!) rather than my ability to create an edible healthy meal! The only subject I got a C in despite being so confident the teacher never came near me in practical lessons simply because I couldn't draw food 🤦🏻♀️ but I could cook a full weeks worth of meals for my family if I wanted age 16 because my parents taught me!

I'm so lucky to have had my upbringing and avoiding these foods.

Rant over! This made me super emotional!