Menopause as a return

Thoughts on going back to the person we were before that surge in oestrogen

Menopause is a life experience that we are all currently in the process of reframing. For a long time it’s been viewed as an ending: the end of fertility, the end of sexiness, or even - if the infamous HRT promoting book Feminine Forever by Robert Wilson is to be believed - the end of being a woman entirely.

Now, menopause ‘warriors’ have emerged to challenge this, and we are bombarded by (largely) helpful messages that menopause is a new beginning; an upgrade; the beginning of our ‘Queenage’; and the birth of a new version of ourselves: the wise woman.

All of these imply a linear version of life, a constant movement forwards. Sometimes this concept can become tiring, as hidden within it is the implication that we must always be working on ourselves as a project, and that if we are not feeling and celebrating our personal ‘growth’ on the daily, we may need a course, a supplement, a retreat, a book, a guru.

As the summer ends and the leaves turn to gold on the trees, it seems like a good time to write about a third way of thinking about menopause - not as an ending, or as an upgrade, but as a return. A cyclical ‘looping back’ in which we rediscover the core person we were, before fertility happened.

As women, fertility - whether or not we have children - is an exciting gift. I currently see it blooming in my teenage daughters and I notice how it opens up their world and energises them to seek adventure, company, excitement and yes, sex. But the flip side of this - and what they and none of us realise at the time of course - is that the whole thing is going to knock them off course and into entirely new orbits, for the next couple of decades at least. And that much of this will probably involve a setting aside of their own needs, hopes, desires.

Oestrogen, in some ways, derails us. It softens our judgement and encourages a more forgiving nature. It blinds us to faults. It urges us to reproduce. Under oestrogen’s spell, we obey, only to feel shocked at the scene that surrounds us when menopause shakes us roughly awake. For many of us, some of the struggle of ‘The Change’ has a ‘morning after the night before’ vibe: why did I do that? what was I thinking? We look at the choices we’ve made and where they’ve led us with fresh eyes, and many of us feel awakened to a sense we’ve been exploited, and determined to be a lot less tolerant. No wonder Robert Wilson, as well as countless other doctors and mental health experts, have explored a variety of ways to numb women of this age and put them firmly back to sleep.

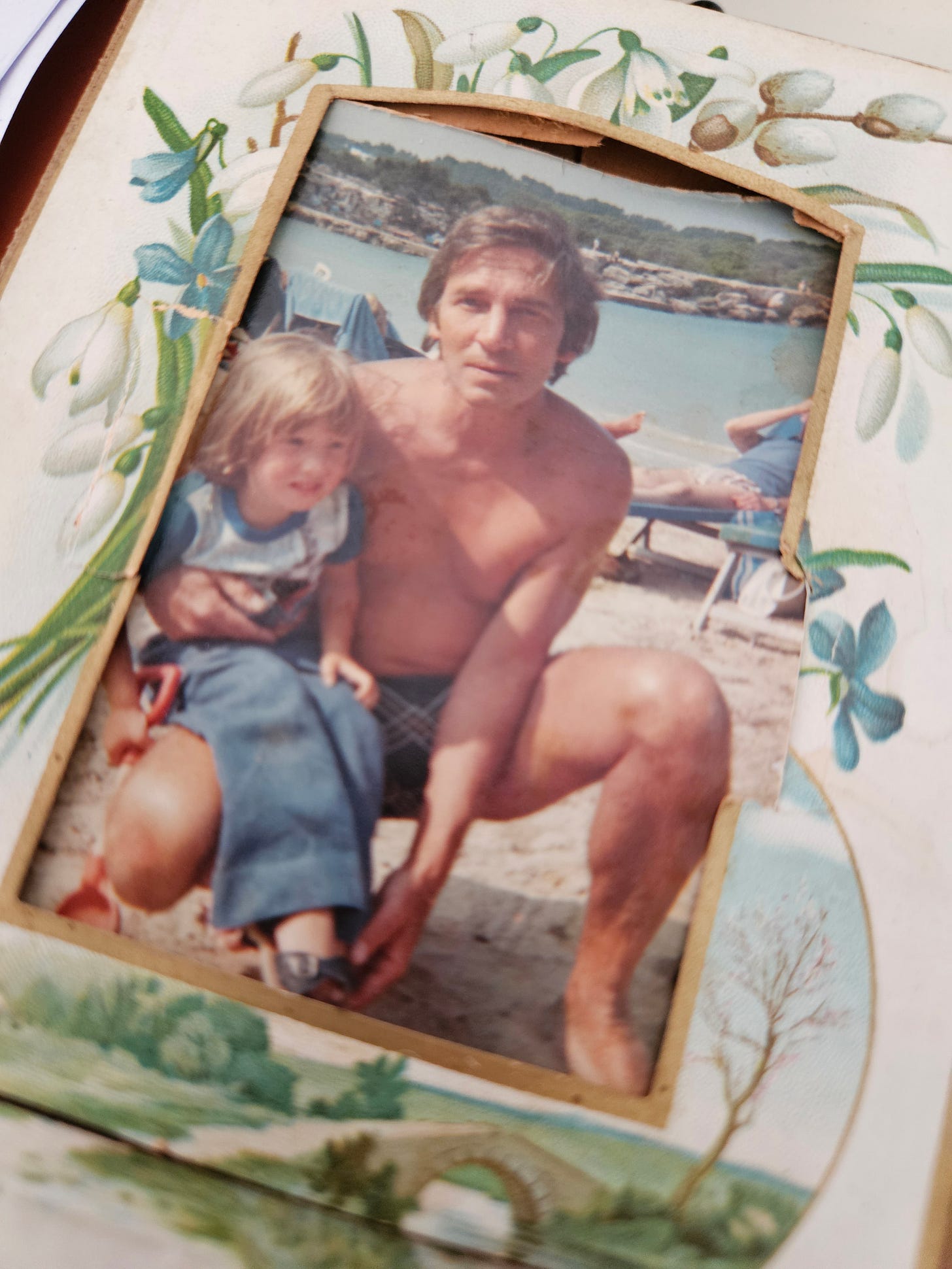

Amidst this time of revision, I also feel a sense of return. Who was that girl in the 1980s, what were her priorities, what were her dreams, before puberty changed her? I remember being her. I remember walking up the little side lane near my house and spending a long time just looking into the hedge and watching baby birds in a nest. I remember my deep never-ending, sibling-like love for my labrador Ben. I remember playing at libraries and arranging books in neat rows. I remember waking early every morning and tearing through detective stories, spy stories, magical stories, any stories I could get my hands on. I read as if there were no time left.

At that point I had no limits on my sense of what I could become. Nor did I particularly think about what I would become, because for the most part, I was absorbed in the present moment, and carefree. When adults asked what I wished to be when I grew up, my answer would depend on what book character I’d most recently fallen in love with: I’d be a nurse, a show jumper, a stable boy, a detective, I really had no idea. Mostly I just wanted to be just a couple of years older than I actually was and heading in a horse and carriage towards a big house where my adventure would begin.

Pre-puberty Milli was called Melinda. Melinda liked animals, playing in nature, playing with dogs, reading books, making up stories, and dreaming. At primary school Melinda got sent for a hearing test but it turned out that she could hear perfectly fine, she was often just unavailable for comment because she was staring out of the window and travelling somewhere much more interesting in her mind. Her head was in the clouds a lot of the time but when it wasn’t, it was in a book. The only time she felt frustrated was when the gap between the imaginary world and the real world was too wide: trying to clear the brambles in my own version of the Secret Garden, for example, was a lot more difficult than Mary and Dickon made out. After half a day of getting my hands scratched and no visible signs of progress, I gave up. I can still remember how sad I felt that day - perhaps my first experience of overwhelm and failure. Life was easier in a book.

Melinda also got in trouble once or twice at her first primary school for ‘answering back’. There was a particularly annoying head boy, I think his name was Jonathan, who seemed completely enormous to me although of course he can only have been about eleven years old. I cannot remember what he was saying when he supervised my class one day, I can only remember the feeling of daring as I spoke up and set him straight, and everyone laughed, and then I got sent to the headmistress. This streak of rebellion continued at senior school where I boarded and would get in trouble for gentle and comical crimes such as impersonating the house matron by putting a pillow up my nightie and waggling my finger at everyone, or chattering long after ‘lights out’. I was naughty, but only a little bit. I would stay up half the night reading Flowers in the Attic or Far from the Madding Crowd by the dim yellow safety lighting in the toilets. At one point I caused a sensation by writing hilarious stories in which a middle aged house mistress we all despised would find love with a handsome gardener. I guess I was a class clown, but never so much that I didn’t do well: I excelled.

Some of the work of menopause, I feel, is to reconnect with that girl. Suddenly now my children don’t need me as fiercely and intensely; I have space. Any mum reading this will know what that simple sentence means: I have space. How much I craved that space in my thirties when my every waking and sleeping moment was crowded and interrupted. Yes yes, I know, now I’m supposed to say how much I miss those little, needy people. Well, I don’t actually. I miss the idea of them. The reality was bloody hard work and I feel more like: yes, it was lovely, but been there, done that, got the t-shirt.

In my twenties, life was equally intensely occupied by the quest to find ‘the one’. I had what they now call a high ‘body count’, falling in love over and over and writing bad poetry about my many rejections. I did not really understand what men wanted; it only seemed like my personality was too much for them, and that once they had had their fill of my beautiful body, my opinionated, vibrant, quick-witted nature was a threat. There were many heartbreaks and betrayals. The biggest love of that decade, the actor Chris Vance, turned out to be an extremely duplicitous narcissist. Others were already in relationships with someone else, liars, jealous and controlling, reluctant to commit, or just plain weird. It was tiring. Another few t-shirts I’ve been there and got and don’t need to get again, anyway.

There is a ‘what now’ feeling about this time of life. There is a pressure to ‘grow’, but what if we already ‘are’. Rather than becoming someone new, maybe we simply need to return to the person we always were, before love, sex, motherhood and oestrogen distracted us? Who was that core person; what pleased her; what were her needs? Were there dreams she had that are yet to be fulfilled? Were there activities she enjoyed that have long been abandoned? Now, there is space for her again. But who was she then, and who is she now?

Returning, we do not always find things as we left them. I remember once coming back from a holiday to discover a starling had been trapped for several days in my kitchen. It had survived by pecking away at the contents of the fruit bowl, shitting liberally everywhere, and flapping around the worktops sending glassware flying to smash in large quantities across the floor. Adult Milli found this to be a bit of a nightmare; Melinda would have found it a great adventure and decided immediately to adopt the starling as a pet and teach it to talk.

Coming back to my core self now I am not and will never be that ten year old, daydreaming wistfully and wondering how hard she would have to practice to learn as many animal languages as Dr Doolittle. Life has wreaked its havoc. But under the broken glass and the rotted fruit peel and the shit, something of her remains. As a mum, I have seen first hand how children hatch out of the egg with a ready-formed personality and a plan. My task now is to remember mine.

Like this post? Lay some love on it by sharing, clicking the like ‘heart’, or subscribing…

I’ve written four books, would you like one?

Milli, your lovely essay brought me to tears this morning.

I’m also sick of hearing “Menopause Queen” reinvention bullshit. I’m tired, bulldozed by the demands of life, work, and caring for young adults and teens and an elderly mom.

I was a lot like you when I was a kid. My whole life was given over to books, a love for animals, and an overactive imagination. I saw the potential for mischief everywhere but was too timid to ever act out.

I’m bolder now, and your point about getting back to that little girl is intriguing. Thank you!

(And whoo boy, I devoured the Flowers in the Attic series. All that incest…yikes)

I love this take on menopause. Beautifully written. I’m so over the Menopause Queen stuff - there’s a big gap between the rhetoric of ‘embracing the wise old woman’ version of ageing, and the anxious, skinny, weight lifting, supplement chasing physical version - which is all about fear of looking old. You’re writing about *who* we are. Superb.