Birth and breastfeeding: do we make free choices?

and other questions raised at the Battle of Ideas

Are women manipulated in their birth and feeding choices, and if so, by who and for what gain? This was the key question I was left with after a very interesting panel discussion on ‘Feeding Babies: Is Breast Always Best?’ at the Battle of Ideas last Saturday.

The panel was chaired by Professor Ellie Lee from the University of Kent, and consisted of me, breastfeeding expert Harriet Rudd, independent policy advisor Rebecca Steinfeld, and University lecturer and co-director of Feed, Dr Erin Williams.

I don’t think it would be unfair to say that Harriet Rudd and myself were the only members of this group of five who were truly ‘pro breastfeeding’ - although both of us would probably describe ourselves instead as being pro informed choice, pro support for women, and pro all women feeding their babies in whatever way they choose for as long as they choose - a claim that all the other panellists would probably make about themselves too. The event therefore raised interesting questions about what a truly pro woman and pro choice infant feeding policy would look like.

Ellie Lee, who chaired the panel, was definitely more on the same page with Erin and Rebecca than with myself and Harriet. Her take, as I understand it, is that both the health benefits of breastfeeding and the risks of formula are overstated, and that women therefore feel pressure to breastfeed because of the persistent messaging that formula milk is inferior. She feels that women’s feeding choices are ‘moralised’, and that truly informed choice could only be achieved by women being provided ‘balanced information about all feeding methods’. To quote from a paper she has written on this:

“Policy…should cease to connect mothers’ infant feeding practices with solving wider social and health problems. Doing so, evidence suggests, has failed to do much to increase breastfeeding rates; has generated a distorted picture of the causes of health and social problems; and has encouraged a situation where many mothers experience being placed under pressure to feed their baby according to priorities laid down by others.”

Each panellist gave a five minute opening talk; some of you will have read mine here last week.

Rebecca Steinfeld will be publishing hers elsewhere, but here is a bullet pointed summary. Unless in “quotation marks”, I am summarising in my own words.

Women deserve properly informed choice, but instead are getting, “an extremely pressurising pro-exclusive breastfeeding policy that is obsessively obsessively focused on increasing breastfeeding rates, undermines women’s reproductive autonomy, is not based in good evidence, doesn’t reflect or support the reality of women’s actual feeding experiences, and harms both women and babies in a number of ways.”

‘Breast is best’ policy causes women to feel guilt and stigma. Majority of women feed formula, and majority feel bad about it.

By framing breastfeeding as a public health issue we undermine women’s autonomy - pressurising them to use their individual bodies for public gain.

“There is little good quality evidence to support the numerous health and non-health claims made about the benefits of breastfeeding.” Emily Oster in particular has debunked most of the evidence to support breastfeeding by pointing out that most studies fail to control for social factors associated with breastfeeding such as more educated mothers and better living standards.

Restrictions on sale and marketing of formula are damaging and causing parents to water it down or get it on the black market, and babies to go hungry.

Pro breastfeeding messaging causes direct harm to babies with insufficient milk intake from exclusive breastfeeding leading to hospital admissions.

Better infant feeding policy would include information that was less biased towards breastfeeding, better support for all choices, the lifting of restrictions on formula purchasing but better still - free formula milk.

Harriet Rudd spoke next and has given me her permission to publish her speech in full:

Breastfeeding isn’t necessarily always best. For a variety of complex reasons. But it is the normal and usual way to nurture babies. As a public health slogan, Breast is best is malicious and lazy because it judges and blames individual mothers. Breastfeeding is a psychosocial activity and a collective responsibility.

But because of our society’s attitudes toward the needs of mothers and babies, the second half of that slogan should be: ‘Breast is best if you can do it on your own, without any help, but if you can't, screw you.' That might sound harsh, but it is the best way I can describe the lived experience of mothers up and down the country.

We are being let down every day by a lack of investment in skilled and timely breastfeeding support. Nobody should be saying breast is best to a new mother and then leaving them to it. But we should say breast is normal, and then work to make it feel like it is.

In the UK we have high breastfeeding initiation rates. 81% of mothers start breastfeeding. Six weeks later it’s plummeted to 24% still exclusively breastfeeding. At six months it is just 1%. We have the lowest breastfeeding rates in the world, which is a public health crisis. Eight out of ten mothers have to give up breastfeeding before they are ready. We need to stop women carrying guilt, shame and regret around their breastfeeding journeys. We need to protect breastfeeding, not promote it. We need to help mothers to meet their own breastfeeding goals, whether that is two weeks, two months or two years.

Easy access to skilled counselling, would nip any problems in the bud and address issues like oversupply, blocked ducts, painful nipples, fast let down or low supply before they become too serious. Because…after the first instinctive feed in the golden hour after birth, breastfeeding becomes a learned skill, which is different with every baby.

On the postnatal ward where I work, about a quarter of mothers need specialist help because either their babies are not latching to the breast, or their babies are latching, but are not transferring milk or colostrum effectively. This can be distressing but the breastfeeding journey can be preserved, with skilled, ongoing support. Breastfeeding is simply not something we are designed to do alone.

Protecting breastfeeding is more challenging than promoting it since it means we have to look at our own part in the equation rather than putting the entire responsibility on an individual, exhausted mother.

Protection puts the onus on those around the mother – her family, her friends and neighbours, her employers, her village, her government. Protection raises awareness of the subtle anti-breastfeeding messaging a woman will be exposed to all her life in the UK, whether it is the blatant lies of formula advertising, a celebrity back on the circuit a few weeks after giving birth, a raised eyebrow from a passerby, or a constant barrage of images of sexualised, surgically enhanced breasts.

A report commissioned by UNICEF UK shows that the NHS would save at least £50 million pounds a year if all mothers breastfed for just three months as there would be less sick babies, less sick mothers, less hospital admissions and less medications needed. It would also save babies lives through a reduction in sudden infant death syndrome.

If breastfeeding is so beneficial, why do we often feel so isolated, embarrassed and awkward when we are carrying out this work?

As a teenager at my girl’s grammar school, I was taught that I could be equal to boys, that I could do what they could do. I was fed the myth of equality on their terms. I could be just like the boys. No one taught me about my own body, about breastfeeding, about what my role as a mother would be, and the profound changes I would undergo.

When my first son was born, I was totally unprepared for motherhood. Shaky and weak with PTSD, asking for help felt like failure, so I struggled alone. I had no idea that it was normal for mothers to actually need mothering in order to be able to meet their babies’ intense attachment needs without burning out.

70% of mothers in the UK experience baby blues. Which could be described as a mini depression. What a way to begin a mothering journey. But traditional cultures understand the plasticity of the postnatal brain and the vulnerability of the postnatal body.

In Zambia, baby blues does not exist. A new mother is never left alone. She is surrounded by female elders and massaged daily, maintaining her oxytocin levels and regulating her nervous system. She is relieved of all responsibilities apart from establishing breastfeeding and bonding with her baby.

Given that newborns can breastfeed every 60-90 minutes day and night for weeks and months, this level of care for the new mother is totally appropriate.

I know that our culture is very different to that in Zambia, but we as a society dismiss dependence and admire independence. We live in a cult of the individual. But our true nature as humans and primates is dependence and interdependence. There is nothing that brings this truth home more starkly than becoming a mother. Of all mammals, our young are the most immature at birth. If mothers are not breastfeeding, a normal human behaviour, we have to ask, what is wrong with our society and how can we change it, not what is wrong with mothers.

Last to speak was Erin Williams from Feed. She is also publishing her speech elsewhere, but I will summarise in bullet points. Again, unless in “quote marks”, this is a summary in my own words.

No disputing that breastfeeding is normal or that it has health benefits, but feels that how we currently support women is failing them. Challenging the current approach can lead to accusations of being anti breastfeeding or pro formula, neither of which she feels apply to Feed.

Infant feeding support in the UK is currently outsourced to UNICEF. The NHS pays “an undisclosed sum of money” to UNICEF who provide policies, training and guidance to NHS professionals via their Baby Friendly Initiative (BFI).

Although the rationale of the BFI is improved health for women and babies, UNICEF only measure success of BFI by monitoring numbers of women breastfeeding, therefore we don’t know if BFI works.

Restricted access to formula because of BFI has a negative impact on the most disadvantaged.

The income stream of UNICEF is dependent on their impact, and their impact is measured by numbers breastfeeding. This is detrimental to women who, in the drive to improve the numbers, are given an unrealistic picture of breastfeeding and a negative view of formula, leading to grief and guilt.

Formula feeding is unsupported and women and organisations like Feed have to fill the gap. Women’s voices are ignored, how is this ‘baby friendly’?

Trust needs to be restored - trust that information given to women about feeding is not done with targets in mind, and trust in women to make informed decisions.

After these opening speeches, there was a rich audience-led discussion. Overall, the audience seemed largely pro breastfeeding, with many women telling either of how they felt they would have liked to breastfeed but were let down by lack of support, or of how they did breastfeed and found it an extremely positive experience. Only one woman talked about her decision to feed formula from the start, and of how she felt this was a positive choice that gave her greater freedom.

As part of my follow up comments I challenged a few of the panel’s points from their talks. Firstly, I challenged the idea that the health benefits of breastfeeding are overstated, citing the proven reduction in ovarian, breast and uterine cancer, and cardiovascular disease in women, and the lowered infant mortality and benefits to the gut microbiome in babies. I stated that the formula fed baby was a gift to the pharmaceutical industries, because of their and their mother’s increased chances of health problems over a lifetime. I also challenged the suggestion that breastfeeding support is ‘outsourced to UNICEF’, reminding the audience of the huge army of unpaid women who prop up the absolutely dire breastfeeding services - or lack of them - in the UK. I disputed a point made by Erin that breastfeeding was an industry just like formula - with the former being one of the worst possible career choices if you want to make money, whilst the latter is a multi-million dollar business. I touched on the link between birth and breastfeeding, since several audience members mentioned their traumatic births. And I ended by making the point that we are currently at a major fork in the road. In a world that is drifting further and further away from ‘nature’ - epitomised by lower and lower numbers of natural birth and breastfeeding but seen in many other areas - we need to decide, what do we want the future of motherhood to look like?

Overall, the experience of this panel was both thought-provoking and frustrating. Listening to people whose views are - at times - a million miles from your own can be hard, but it’s also refreshing, because it challenges your own thinking, sometimes allowing you to confirm your existing beliefs, sometime causing you to shift. In particular this session caused me to think more about whether women are currently making truly free or truly informed choices about birth and breastfeeding, and if not, who is leading them in certain directions, perhaps directions that may be detrimental to them, and why?

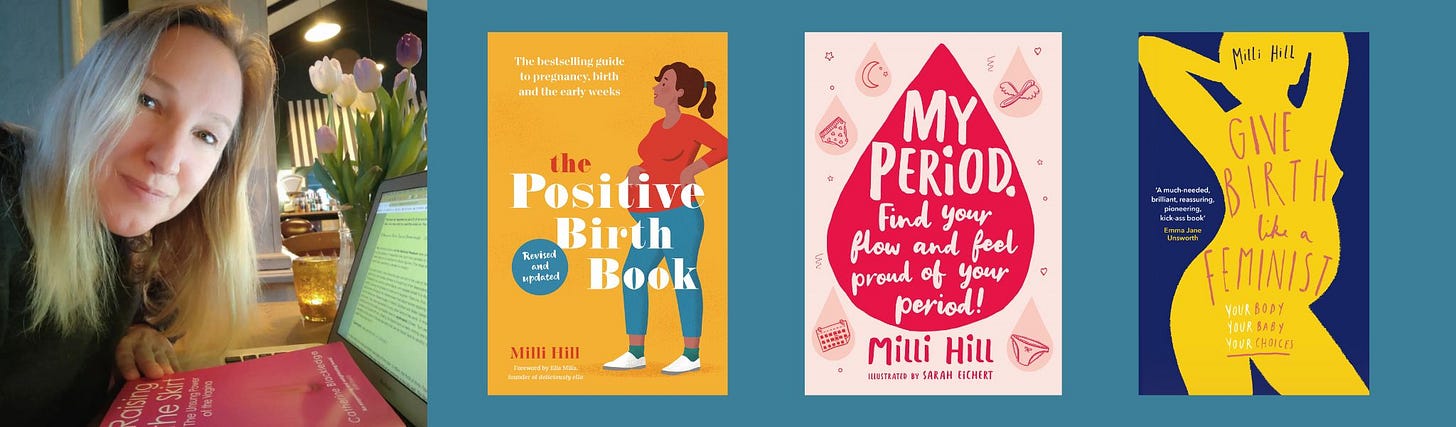

This question interests me because it’s an accusation that could - and has been - levied at me in the past. Birth safety campaigners, for example, have said that I have a ‘natural birth agenda’ (or am even part of what they call the ‘cult of natural birth’), that is giving women a false impression of birth or even putting them at risk. Some (not many but some) Amazon reviews of the Positive Birth Book have said that there is too much emphasis on natural birth and breastfeeding - which is deliberate on my part because a) many women want these things and b) they are evidence based and c) they are hard to come by. But I have thought long and hard about whether I’d right on this, because the secret to not being in a cult is actually to ask yourself difficult questions! So I ask myself: are women like me, who say they are trying to help women, or even claim (as I do) to be feminist in our actions, actually doing the opposite, and making women’s lives harder?

On the other hand, what agenda do others have? In the week before the Battle of Ideas, the organisation Feed, whose views were supported by 50% of the panel and the chair, announced a new campaign ‘Formula for Change’, to have BFI restrictions on infant formula lifted, so that, ‘cash strapped families can afford to feed their babies’. I am not sure that letting people get formula with their clubcard or foodbank vouchers is the solution to poverty the world needs right now. For the record, I do support Rebecca Steinfeld’s proposal of free formula, but I also think that even this has to happen in tandem with a massive hike in funding into maternity and postnatal services, and proper support for women who genuinely do want to breastfeed. Without a campaign for this bigger picture stuff, the Formula for Change agenda is a simply a gift to formula companies. Are they supporting it in some way? Even if they are not, they are surely cockahoop about it.

Today someone sent me this article from the Maternity and Midwifery Forum, about the appalling state of maternity care in the UK. To pick out a few stats: maternal mortality is up 15% since 2009; the leading cause of maternal death is suicide in the first 12 months; seven out of ten women are psychologically traumatised by childbirth; 65% of maternity services are rated inadequate. I guess what it made me think (apart from ‘How f***ing depressing’) is that if there is a cult of natural birth it’s not very bloody effective. It’s the worst flop of a cult ever.

The counter-argument of most of the Battle of Ideas panel to this would probably be that although the Cult is not achieving its aims, it IS making women feel absolutely terrible about their epidurals and caesareans, and should therefore be shut down anyway. To me, this claim that those arguing for the ‘natural’ approach to birth and breastfeeding are simultaneously weak, ineffective AND powerful enough to cause substantial damage, seems a great way for the Big Guy to squash the Little Guy.

But what do you think? This debate needs more viewpoints, so I’ve made this whole post free to access and the comments open to everyone, not just my paid subscribers. I look forward to hearing your respectful discussion in the comments below. Milli x

Please consider supporting my writing by becoming a free or paid subscriber. You’ll get all my posts delivered straight to your inbox or via the brilliant substack app, including my weekly post The Word is Woman, where I document examples of the erasure of women from language. Thanks for your support, it really helps.

Like this post? Please do share it.

cracked nipples. mastitis. my pretty girlish breasts suddenly becoming enormous and blue veined with massive brown nipples. 4 babies. bedding in. reading novels. a tiny hand palpitating. those angelic eyes. the closeness. the tenderness. the magic of it. bloody marvellous. i loved breastfeeding.

Thanks so much for this write-up of the panel.

I am so glad you and others are speaking up, because the end goal in trying to make you ashamed for speaking up is to completely silence you. And if you are silenced, then options for women contract because they won't know there are alternative viewpoints to that which is mainstream. So please do not self-silence!

At the same time you are completely right that we do not support mothers after birth! Healing from childbirth and successfully beginning the mother-baby dance of breastfeeding requires a lot of mother-to-mother care. Even so, it must be recognized that many new mothers do not want others to be in their home after birth. That, too, is a delicate dance between privacy and support.

In sum, we must continue to speak out for the ideal--that is non-negotiable. And then we must make information and one-on-one support available for women who are currently post-partum, though we must also respect their wish for privacy.